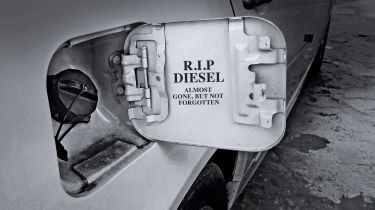

Death of diesel: what really happened to our one-time favourite fuel?

The number diesel cars on UK roads has dropped dramatically over the last ten years. We look at the reasons why and wonder if there's any sign of a comeback

There is now less than a third of the number of diesel cars on sale than a decade ago, but a limited supply and what appears to be a consistent demand seems to prop up the used values of vehicles that utilise the black pump.

As of 2025 there are 91 individual diesel models on-sale, compared with 118 the previous year and 240 a decade prior in 2015 – the year of the infamous Volkswagen ‘Dieselgate’ emissions scandal.

While diesel powertrains were once ubiquitous no matter what price point or model segment you were looking at, the minimum point of entry is now relatively high; the cheapest new diesel model currently available in the UK is the Citroen Berlingo MPV (£27,055), with four of the top-selling models in the UK throughout first half of 2025 being from Land Rover and all starting from more than £45,000.

It’s no surprise then that new diesel sales now account for a minuscule segment of the market; diesel enjoyed its biggest market share in 2012 during which well in excess of a million were sold, accounting for just over half (50.8 per cent) of vehicles sold that year. This dipped slightly in 2015 to 48 per cent, but has since plummeted to just six per cent in 2024 – forecasts suggest it’ll fall further to five per cent by the end of this year.

If you still have love for diesel, there are plenty of used diesel cars available for sale via our Buy A Car service, including a used Volkswagen Golf for under £5,000 and a used Range Rover Evoque for less than £7,000.

Why are there so few diesel models on sale nowadays?

While it’s easy to blame the fallout of Dieselgate, ultimately the reason why there are now drastically fewer diesel models on sale is a lot more nuanced than a simple single cause and effect.

Firstly, it’s worth pointing out that the market was once oversaturated with diesel models, with the powertrain seeping its way into segments which didn’t necessarily lend themselves to its inherent characteristics.

“Historically, there were products in the marketplace that really had no reason to be diesel,” Nothard explained. “There was no rationale for things like diesel city cars – they don’t need the torque as they won’t be towing a caravan and similar MPG can be achieved in a petrol.”

With the price difference between a petrol and diesel equivalent typically costing the consumer an extra five to 10 per cent more, it didn’t really make sense for the lower end of the market, resulting in the top-heavy nature of new diesel cars availability today.

Following this realignment, ‘diesel’ gradually became something of a dirty word – no doubt due to the emissions scandal – while climate activists, as well as government officials, began pushing for electrification in order to reduce the carbon footprint of our roads.

Yet, while electric cars are the final destination – low car tax rates mean EVs are already taking the lion’s share of fleet sales, which were once taken up by diesels – Molden believes that hybrid cars are, in his own words, “the real killer for diesel”.

Diesel cars typically incur a small price uplift over their petrol equivalent for CO2 savings of around 10-15 per cent. “A petrol hybrid, however, for about the same increase in cost of the vehicle, you get 25 to 30 per cent CO2 reduction,” Molden says. “EVs can give about a 50 per cent reduction in CO2, but they generally cost around 30 to 40 per cent more” – although this gap continues to narrow as manufacturers invest more in electrified technology.

What about diesel hybrids?

So what about diesel hybrids, then? Surely a combination of diesel and hybrid technology would be the dream in terms of fuel economy and tailpipe emissions?

Well, the reality isn’t quite so straightforward, with Molden firstly pointing out: “The incremental emission savings on top of what you get from a diesel are actually relatively small.”

Furthermore, there is also the issue of the heat generated by diesel engines; while the internal operating temperature is higher than an equivalent petrol unit, the use of Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) systems reduces the heat emitted by the exhaust.

With this in mind, Molden explained: “The AdBlue system requires heat and because the engine is cutting out all the time, you don't get as much heat as you need. So the two technologies almost clash.”

Of course, it’s not impossible to create a solid diesel hybrid; the Mercedes E 300 de uses a 2.0-litre diesel plug-in hybrid engine and is claimed to return 176.6 mpg – whether it will do so in the real world, however, is unlikely, but the figure is indicative of a very efficient engine.

Unfortunately, other than mild-hybrid variants, the Merc is the only plug-in hybrid diesel on-sale and has been for some time, indicating that it’s unlikely we’ll see this type of powertrain take off anytime soon.

When will diesel die out?

The question of when diesel will die out is met with mixed answers depending on who you ask. Ultimately, while the fuel type will inevitably meet its end before 2035 as after this point we’ll only be allowed to purchase fully-electric cars from new in the UK, whether brands will stop production before then is another matter.

Nothard and thus Cox Automotive’s projection is that diesel will become extinct – that is, in the new-car market – well before the 2035 deadline. “Before 2035 I predict there will be the OEMs looking at the market wondering what is the point in manufacturing diesel products for the UK market,” Nothard estimates.

| Year | Diesel % share |

| 2015 | 48% |

| 2016 | 48% |

| 2017 | 42% |

| 2018 | 32% |

| 2019 | 27% |

| 2020 | 20% |

| 2021 | 14% |

| 2022 | 10% |

| 2023 | 7% |

| 2024 | 6% |

| 2025 (forecast) | 5% |

| 2026 (forecast) | 5% |

| 2027 (forecast) | 3% |

| 2028 (forecast) | 2% |

In fact, Cox Automotive believes that by 2028, diesel market share could be as low as just two per cent of overall sales. After this point and with Chinese manufacturers flooding the market with petrol hybrids and full-EVs, legacy brands may decide to pull the plug soon after given the tight margins of building a completely separate powertrain in such small numbers.

However, there are those – including Molden – who think the death bell has already chimed for diesel. “I think diesel is dead in light duty – cars and small vans,” Molden said. “This is partly because of the reputational hit, but also a petrol hybrid is just more effective at reducing CO2 per pound you have to invest in it.”

Diesel won’t be gone in its entirety, though, because it will live on for at least a while in heavy duty applications before the likes of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles take over the reins. “Specifically where the crossover point will be, whether it'll be in the van sector or the truck sector will depend on the economics,” says Molden.

What does this mean for used diesels?

The future for the used-diesel sector appears to be just as uncertain as for new cars given how consumer demand appears to persist – albeit in smaller numbers than before – while the flow of pre-owned cars entering the market continues to slow.

Looking at used values of the four most popular used diesel models on Auto Express’ Buy A Car service – the Ford Kuga, Range Rover Evoque, Mercedes A-Class and Volkswagen Golf – we can see that the average price of a three-year-old used example has remained steady over the past few years, in some cases actually rising.

| 3-Year-Old Car Price | Ford Kuga | Range Rover Evoque | Mercedes A-Class | Volkswagen Golf |

| 2025 | £19,940 | £28,916 | £22,109 | £20,516 |

| 2024 | £19,934 | £27,245 | £20,831 | £23,156 |

| 2023 | £19,851 | £26,775 | £19,822 | £17,644 |

| 2022 | £19,703 | £37,353 | £23,142 | £18,452 |

| 2021 | £20,484 | £30,923 | £21,448 | £19,247 |

In fact, according to Cox Automotive, diesel residual values are not all that far off a petrol or hybrid equivalent; despite all of the negative press, diesel models receive, cars with this type of engine typically retain around 51 per cent of their original asking price after two-to-four years of ownership. This is only slightly less than the 53 per cent and 58 per cent retained by hybrids and petrol cars respectively and more than the average EV (36 per cent) or plug-in hybrid (46 per cent) residual value.

Things could improve, however, as the pool of new diesel cars narrows and pushes further upmarket. This could, in turn, increase residual values of used diesel cars, with Nothard explaining that: “The choice of nearly new diesels is going to be few and far between. So if you've got one, you can probably ask a good premium for it.”

All of this is highly dependent, of course, on government legislation because this could force people out of their diesel cars and into hybrids and EVs through additional taxation and road restrictions. This could come in the form of additional VED tax brackets, an expansion of ULEZ to other major UK cities or even a form of the Crit’Air scheme found in France, in which certain vehicle types are banned from entering designated areas entirely.

Considering this, Molden believes that “Any diesel car from the ‘Dieselgate generation’ (before 2018) is beyond help and will be dead pretty soon as they still have the problem of dodgy treatment systems”. He added: “Cars from the seven years between then and now could become low carbon with synthetic fuels, but I’m not confident how long they’ll be allowed on the road with growing restrictions.”

Did you know you can sell your car through Auto Express? We’ll help you get a great price and find a great deal on a new car, too.